Part One

Steve Sailer recently compared the Alt-Right to punk rock. It’s an apt analogy in more ways than one, and as someone whose adolescence was informed by that music, it’s one that I readily appreciated. I’ve long thought of writing an essay about the implicit whiteness of punk and hardcore music, especially since it’s a rather under-appreciated genre on the AltRight.

That’s partly understandable since a lot of punk rock is utterly nihilistic and degenerate – indeed, punk got its start by unabashedly wallowing in the filth of New York’s urban decay of the 1970s. But it can be seen in the larger context as a reaction to an already degenerate society, much the way Julius Evola regarded the Beat movement a few decades prior.

Music journalist Simon Reynolds writes:

“In ‘The White Noise Supremacists,’ a controversial Village Voice essay published in 1979, Lester Bangs pointed out the uncomfortable connections between the near total absence of black musicians on the CBGB scene, punk’s penchant for using racist language (all part of its antiliberal, we-hate-everybody-equally attitude), and the perilous ambiguity of punk’s flirtations with Nazi imagery. Factor in the sheer unswinging whiteness of punk rock and most New Wave music, and you had a situation where, for the first time since before the 1920s hot-jazz era, white bohemians were disengaged from black culture. Not only that, but some of them were proud of this disengagement. Just a week before the Bangs essay, the Village Voice profiled Legs McNeil of Punk magazine. Writer Marc Jacobson discussed how McNeil and his cohorts consciously rejected the whole notion of the hipster as ‘white negro’ and dedicated themselves to celebrating all things teenage, suburban, and Caucasian. Years later, McNeil candidly discussed this segregationist aspect of punk in an interview with Jon Savage: ‘We were all white: there were no black people involved with this. In the sixties hippies always wanted to be black. We were going, “- fuck the Blues, fuck the black experience.”’ McNeil believed that disco was the putrid sonic progeny of an unholy union of blacks and gays. Punk’s debut issue, in January 1976, began with a rabid mission statement: ‘Death to Disco Shit. Long Live the Rock! I’ve seen the canned crap take real live people and turn them into dogs! The epitome of all that’s wrong with Western civilization is disco.’”

Simon Reynolds, Rip It Up and Start Again, Chapter 9: “Contort Yourself: No Wave New York”

If you watch the documentary American Hardcore about the 80s hardcore scene, you’ll hear this same sentiment about white kids wanting to move away from black culture and have something of their own. Of course, it’s always couched in anti-racist language, made out to be about not wanting to culturally appropriate black music or some such thing. But even if that is the legitimate sentiment, whites will find themselves in a double bind, since rejecting black culture can easily be seen as racist in motivation, just as embracing it is also racist since it’s usually characterized as a kind of theft (such as with the recent denunciations of Justin Timberlake.) Whites are damned if they do and damned if they don’t, and this impossible situation is no small cause of the present discontent.

The manifestations of anti-liberalism and white racialism in early punk rock ranged from merely failing to pay heed to the absolute prohibition of the swastika (The Sex Pistols, The Dead Boys) to songs like Black Flag’s “White Minority” and Minor Threat’s “Guilty of Being White,” the authors of which vehemently insist that they were completely tongue-in-cheek, ironic, satirical, or whatever other description allows them to keep their antifa credibility and avoid having to acknowledge the legitimacy of the feelings they expressed. (In contrast, non-white journalists like the New York Times’ Kelefa Sanneh are more honest in saying that 1980s hardcore punk was “among other things, the sound of whiteness under siege.”) And because such songs could never be written by anyone remotely near the mainstream today, in a culture that has moved considerably leftwards since 1980, they continue to haunt their creators, who keep having to “whitesplain” them to new generations, much to their chagrin and embarrassment I imagine.

“White Minority” was a song by Black Flag (named after the anarchist symbol) from 1980, written by founding member Greg Ginn. It goes:

We’re gonna be a white minority

All the rest will be the majority

We’re gonna feel inferiority

Gonna be a white minority!

White pride –

You’re an American

I’m gonna hide – anywhere I can.

Gonna be a white minority

Better believe it’s a possibility

Just wait and see

We’re gonna be a white minority.

Ginn has always said that he wrote the song to ridicule the concern that it expresses, and there is no reason to doubt him on that, especially since the song was usually sung by a Latino singer before the band settled on Henry Rollins as their main frontman. The irony is that, regardless of intent, the lyrics proved to be prophetic, as a 2015 Washington Post article about American demographic change since 1980 shows. Indeed, in California, where the band was from, whites already are a minority. If young punks thought it was funny to mock concerns about impending white displacement because it seemed like it could never happen, the joke was ultimately on them.

Black Flag can be seen performing the song in Penelope Spheeris’ 1981 documentary about the L.A. punk scene, The Decline of Western Civilization, recently released on DVD. The Spenglerian title of the film came from Germs’ singer Darby Crash, who was heavily influenced by Spengler’s magnum opus, and who openly called himself a Fascist.

Around the same time, on the other side of the country, Minor Threat recorded “Guilty of Being of White.” Written by Ian MacKaye, the lyrics stem from MacKaye’s experience as a white minority in a majority black school in Washington D.C., an experience he shared in common with Henry Rollins:

I’m sorry – for something I didn’t do

Lynched somebody – but I don’t know who

You blame me – for slavery

A hundred years before I was born

Guilty – of being white

I’m a convict – of a racist crime

I’ve only served – nineteen years of my time

MacKaye now describes the song as “anti-racist” since he felt that blacks were being racist against him. Apparently, he didn’t get the antifa memo that blacks can’t be racist no matter what and everything they do is an appropriate and excusable response to oppression. Indeed, MacKaye has been taken to task by the Punk Rock Thought Police for the song’s lack of political correctness ever since he wrote it.

In a 1983 roundtable discussion with two other musicians, including the leader singer of the far-left band MDC (Millions of Dead Cops), MacKaye explained why he wrote the song:

“I live in Washington D.C., which is 75% black. My junior high was 90% black. My high school was 80% black, and throughout my entire life, I’ve been brought up in this whole thing where the white man was shit because of slavery. So I got to class and we do history, and for 3/4 of the year slavery is all we hear about. It’s all we hear about. We will race through the Revolutionary War or the founding of America; we’d race through all that junk. It’s just straight education. We race through everything, and when we’d get to slavery, they’d drag it all the way out. Then everything has to do with slavery or black people. You get to the 1950s, they don’t talk about nothing except black people. Even WWII, they talk about the black regiments. In English, we don’t read all the novelists, we read all the black novelists. Every week is African King’s Week. And after a while, I would come out of history class, and this has happened to me many times, like in junior high school, and you know that kids are belligerent in junior high, and these kids would jack my ass up and say, ‘What the fuck, man, why are you putting me in slavery?’”

“And I’m just saying I’m guilty of being white – it’s my one big crime. That’s why I get so much fucking shit at school, that’s why I cannot get on welfare in Washington, most likely. That’s why when we took the PSATs, when Jeff checked off the black box, he got awards, he got scholarships, he got all kinds of interest, but when he admitted he was white, all that was gone. Just like that. It’s ridiculous. I don’t think it’s fair.”

MDC vocalist Dave Dictor then goes on to comment about the history of slavery and the oppression of the black race. MacKaye responds:

MACKAYE: But what is guilt going to lead to? … if someone made you constantly feel guilty, what do you think that may result in?

DICTOR: A resentment …

MACKAYE: Thank you. And what would that resentment lead to? You just go right back. They’re going to beat me over the head about African kings and stuff to the point where I’m going to say “well, fuck the African kings. And fuck the black people too. Fuck all this shit.’ … It’s an unfortunate thing, but when I’m in Washington D.C., I’m the minority, so I have a totally different view. … [I]f I’m walking down the street and I see a whole lot of black kids coming up the street, I know from my experiences, I know that there can be trouble. I know someone can say, ‘Oh, you’ve been bred to hate black people.’ But if I’m walking down the street and I see a bunch of rednecks coming down, I know even more that my ass is about to get fucking kicked. But people don’t jump on me for hating rednecks …

Another Minor Threat song with a lasting influence on the punk scene was “Straight Edge,” which has the distinction of spawning an entire social movement from just one song. Straight edgers were a fixture of the hardcore scene in the 80s and 90s, and represented something very different from the punks of the 1970s.

From Punk to Hardcore

If punk was ultimately a nihilistic reaction to the decadence of the 1970s, then its transformation into hardcore punk in the 80s was a step towards positivity, towards creating a scene with healthier values, rather than merely wallowing in self-destruction as so many of the original punks were wont to do. Straight Edge, for example, rejected punk’s ethos of alcoholism and drug abuse in favor of an ethic of sobriety, self-care, and moral uprightness (even if that was sometimes confused with moral uptightness and all-around priggish behavior, as anyone ever accosted by a straight-edger for drinking a beer or smoking a cigarette can attest.) Considering the huge problem of drug abuse and addiction among poor white youth today, the fundamental message of Straight Edge is as relevant as ever.

Furthermore, many hardcore bands’ lyrics often contained messages of encouragement and hope, of keeping it together in the face of adversity, of standing strong and proud, of not giving in to the decadence and decay all around, but rather building something positive. The audience for these words was mostly poor white kids, utterly lacking in any kind of wise guidance from their family or environment. Whatever its faults (including lack of musical ability, aversion to melody and beauty, and a general tendency to YELL! instead of sing) hardcore was an attempt by a neglected generation – the children of the baby boomers – to create some sort of structure amidst the chaos, to salvage something positive amidst the ruins of the sixties.

Another sub-genre of hardcore was, of course, Oi! and RAC (Rock Against Communism), explicitly pro-white and usually associated with the skinhead movement. I’m not an expert on this scene, and so I’ll refrain from commenting on it here, as I’m sure there are plenty of more qualified writers on the subject than myself. But the flip side of the emergence of explicitly racist hardcore punk was the emergence of explicitly anti-racist and anti-fascist punk at the same time. Anyone familiar with the genre can see that this is the form of the music that came to predominate. While being illiberal may have been an acceptable anti-establishment pose during the Carter administration, anti-conservatism became the new order of the day (or rather, disorder of the day) during the Reagan years. By the time the 80s ended, ten years of growing older while hating Reagan and Bush led easily and effortlessly into becoming full-fledged 90s liberals. A good example of this transition is Henry Rollins, who I’ll critique a bit in Part Two of this article.

Part Two

Henry Rollins’ Muscular Liberalism

When David Cameron coined the phrase “muscular liberalism” years ago, I like to imagine that he was thinking of Henry Rollins, who has long embodied a thoroughly peculiar combination of party-line leftism and masculine aggression. Rollins went from being the lead singer of Black Flag, to fronting his own Rollins Band in the 90s, to being a successful indie author and owner of his own small publishing company, to being a film and television actor and now a regular columnist for L.A. Weekly. Like the Sixties radicals before him, he has gone from rebelling against the system to being a part of it – though also like his long-haired forebears, he seems unaware of this fact.

Though I listened to some of Rollins’ music in my youth, these days I often find myself irritated by some of his comments and interviews. Maybe it’s because of the incongruity between his personal aesthetics and his expressed opinions – the guy is into close-cropped hair and weight-lifting, yet his politics are all the typical touchy-feely liberal sentiments that one expects to hear from hippies and HuffPo “male feminists.”

In a recent article, entitled, “White America Couldn’t Handle What Black America Deals With Every Day,” Rollins says:

“If white America experienced a fraction of what black America deals with regarding law enforcement, incarceration, the court system, employment and countless other facts of life, they would immediately and collectively lose their minds.”

He then goes on to establish his credibility as one of the good white people, because he used to hang out with rapper and actor Ice-T.

“I learned another lesson many years later, in 1991. I was on the first Lollapalooza tour. It was one of the best summers of my life. I spent a lot of time hanging out with Ice-T. We talked almost every day. He is one of the most articulate and intelligent people I have ever met. I wish I had a teaspoon of what he’s got. I also spent time with his bandmates and crew.”

This is how white liberals talk about black people: First, they signal their own anti-racist virtue by showing that they easily and effortlessly bond with blacks. Then, they praise them to the skies. Whenever they meet – or, far more likely, merely hear about – a black guy who is not a stereotypical thug idiot (even though Ice-T got famous by representing a stereotypical thug on his records and in films) they will heap accolades upon him saying, “OMG, he’s, like, soooo smart. He speaks soooo well.” (Echoes of Obama ’08…) What they actually mean is: “… for a black guy.”

The essence of the white liberal attitude towards blacks is patronization, which is why they will never hold blacks to the same standards of behavior to which they hold whites – because they unconsciously regard blacks as children or animals who are incapable of living up to them, and who therefore require special treatment.

White liberal patronization of blacks is also mostly patronization from a distance, as in the old joke about the difference between American whites in the north and south: “Southerners say, ‘We don’t mind blacks livin’ next door, as long as they ain’t uppity.’ And northerners say, ‘We don’t mind blacks being uppity, as long as they don’t live next door.'” Of course all the Hollywood stars and starlets support Black Lives Matter, no matter all its thuggery and buffoonery – because they live in Malibu, not Compton.

Rollins continues:

“On days off, or when our buses would pull into the same place, we would eat together. All his [Ice-T’s] guys wore gold. I have no idea what a necklace is worth, but it all looked expensive to me. When we went into places, white patrons and staff tripped on these guys. This is when I understood one of the reasons for the visible display of wealth. My whiteness assured them that I could pay for my meal. Ice-T and his guys had to demonstrate their ability to pay by literally wearing a show of wealth.”

No, Henry, the white patrons didn’t “trip” (hey, don’t culturally appropriate black slang!) because they were worried that your black friends might stiff the restaurant on the food bill. I have some favorite restaurants that I’m quite fond of, but I’ve never worried on their behalf that someone else might dine-and-dash. They were worried because those guys were probably dressed the way that guys in gangsta rap videos dress, in which they often brandish guns and perpetuate an image of themselves as cold-blooded killers. You can’t make yourself famous saying “I’m a killer! I’m ruthless!” and then expect people to treat you like a harmless nice guy, especially when those people have never seen or heard of you anywhere except through your media persona.

As Jack Donovan writes in Becoming A Barbarian:

“It makes perfect sense to assume that a black man on the sidewalk who is outfitted like the stereotype of an urban street thug will act like an urban street thug. He’s signaling in-group affiliation and identifying himself with urban street thugs. If he was wearing a cardigan sweater with a button-up shirt sitting in a college classroom, you might not worry as much. You might be wrong about either one, but based on the information available, the odds are in your favor.”

Furthermore, if it had been 1981 and not 1991, Rollins might have went into the same restaurant with his white punk rock friends – and probably would have gotten a similar response, because some of those guys would have had spiky blue hair and safety pin earrings and generally would have been dressed like extras from Night of the Living Dead.

People are alerted and unnerved by difference, by what is unfamiliar. It’s a perfectly natural, biological response. But in the worldview of liberals, noticing difference is a thoughtcrime (hat tip to Steve Sailer again.) Instead, one should only notice when others notice difference, because obviously the only reason someone might notice difference is because they are an evil, vicious hater. This is the absurdity of the leftist view, in which a kind of perverse hypersensitivity is the supreme virtue: Don’t notice the natural diversity of human nature. But be ever vigilant for others who do notice it, and be sure to shame them for it.

The article goes on to speak of “the two Americas,” a notion Rollins may have gotten from liberal political scientist Andrew Hacker.

“When I really started to understand the two Americas was in third grade. On the last day of school, we were all told if we had passed or failed for the year. There were several kids older than me in my class. They had already been held back and were getting older as their education stagnated. When some of these kids were told that they had not passed, the expression on their faces didn’t change.

“Earlier that year, in the play area one day, kids had lined up for free bag lunches that were handed out. There were more kids than lunches. One kid put a pencil through the palm of the kid who got the last one. We all stood there and watched as he screamed.

“It was in this year that I understood that my life in America was going to be different, not only because of the color of my skin but because of the advantages that came with it.”

I really don’t understand what Rollins is trying to say here. If some kids are repeatedly failing the same grade, the most likely explanation is that they are not good students, either because they lack intellectual ability, or because they have some kind of personal or emotional difficulty which interferes with their learning. Is Rollins suggesting instead that these kids performed as well as the kids who graduated, but were held back because the school was racist and refused to pass them out of spite? If so, he gives no indication of that.

As for the free bag lunches story, it doesn’t seem to be relevant at all. Were the lunches only given to the white kids? Highly unlikely, not least of all because the school was mostly black, as Rollins says later. But if so, is he then saying that a black kid stabbed a white kid with a pencil because he didn’t get a bag lunch? Not a very good story to inspire sympathy for black youth.

As for the “advantages that came with” his white skin, what were they, exactly?

“I went to a school in Washington, D.C., with mostly African-American kids who were bused in from different neighborhoods in the same city. It was a constantly harrowing experience. I got picked on for the color of my skin. Pushed into the urinal, head slammed into the water fountain, shoved down the stairs. It was miserable.”

That doesn’t sound much different from the kinds of experiences that led Ian MacKaye to write “Guilty of Being White.”

So let’s review the examples of black and white behavior in Rollins’ article. Blacks: picking on a kid for being white by pushing his head into a urinal, slamming his head into a water fountain, and pushing him down the stairs. Whites: “tripping on” a group of black guys who walked into a restaurant. Clearly, then, the whites are the villains, because, as I stated earlier, white liberals will never hold blacks to the same standards to which they hold whites.

Henry Rollins is an interesting case because, in addition to the abuse he suffered from his black classmates as a child, one of the important events in his life was the murder of his best friend Joe Cole, by young black males with guns. From Wikipedia:

“Cole and Henry Rollins were assaulted by armed robbers in December 1991 outside their shared Venice Beach, California, home on Brooks Avenue in the Oakwood district. They had attended a Hole concert at the Whisky a Go Go and were returning home after having stopped at an all-night grocery store when two armed men – described as African-Americans in their 20s – approached them demanding money. Angry that Rollins and Cole had only $50 between them, the gunmen ordered the two men to go inside their house for more cash. Rollins entered at gunpoint. However, Cole was killed outside after being shot in the face at close range while Rollins escaped out the back door and alerted the police. The murder remains unsolved.

“In a 2001 interview with Howard Stern, Rollins … speculated that the reason they were targeted may have been because days prior to the incident, record producer Rick Rubin – who was a fan of Rollins Band – had requested to hear the then newly recorded album, The End of Silence, and turned up and parked outside their Venice Beach home in his Rolls-Royce, carrying a cell phone. Because of the notoriety of the neighborhood, Rollins suspected that this would bring trouble because of the implication that they had a lot of money in the home; he even wrote in his journal the night of Rubin’s visit: ‘My place is going to get popped’.”

This is a terrible tragedy that I wouldn’t wish on anyone. But I don’t think that the solution which might prevent further incidents like it is liberalism, muscular or otherwise.

It’s said that a conservative is a liberal who’s been mugged by reality. But Rollins goes against the grain, having clung to, or even doubled-down on, his leftist beliefs in spite of being a victim of black criminality, and earlier having been bullied by black kids at school. Without presuming to psychoanalyze a man I don’t know, I suspect that the only way one can think in this way is through willful repression of one’s instincts and feelings. And indeed, white liberalism is exactly that: the forced repression of one’s normal and healthy instincts of self-respect and self-preservation. One need only look to present-day Europe and its examples of white victims of non-white crime who feel more guilty than their attackers.

But instincts and feelings, though repressed, cannot be eradicated. Maybe that’s part of why I liked Rollins’ portrayal of “white supremacist” AJ Weston in Sons of Anarchy. Weston was of course written as both evil and foolish, as both a rapist and also the wearer of a very childish and clownish tattoo that says “I Kill Niggers.” (Couldn’t they at least have made it a sticker on his gun or baseball bat that said “This Machine Kills Leftists” or something, a la Woody Guthrie?) But he was also the most die-hard true believer of all the racialist characters on the show (which is why he is portrayed as evil and foolish), giving voice to a radical right worldview in several memorable scenes, such as when he says:

“I just pulled my six-year-old out of T-ball ’cause I found out they’re giving trophies to every boy on every team for simply playing the game. Trophies should be earned. Teaching children that everyone’s equal is a dangerous philosophy.”

Then, after shaming the man he is talking to, who is ostensibly a fellow racialist, for hiring Mexican workers rather than whites because they are cheaper, Weston looks him dead in the eye and says, “Never put money over race.”

Rollins himself said that Weston “has no redeeming social qualities, except that he likes his kids. Past that, he’s incorrigible and awful.” In contrast, though, he feels no need to make such a moral denunciation of his latest on-screen character, a serial killer named Bernard in The Last Heist:

“I read the part and I thought I had a little idea for it that he would be friendly and smiley and very lethal. The preparation was basically living with the undeniable belief that what I was doing was the right thing to do. Killing people, yeah, but I’m sending them to a better place. If you were to look at me and go, ‘You’re a horrible person.’ ‘No, no, no hold on a minute, I’ll help you, too.’ The only thing that gets in my way is people going, ‘Ow, ow, you’re cutting the eyes out of my head.’ ‘If you’ll just shut up and let me do my work, I could get through this a little quicker.’

So serial killers can be laughed about, and can also be kind of understandable if you try to see things their way for a moment. But racists are just … eww, as Rollins says again in this stand-up routine about his experience with Sons of Anarchy, in which he really goes out of his way to distance himself from the Weston character. “What about me, says to you: White Power!?” he asks. Well, Henry, you’re a physically strong, reasonably intelligent, and successful white man. You’re white, and you have some power. What’s wrong with that? (Also, you look like a skinhead, which is why you were picked to play one. Duh.)

The fact is that Rollins’ dismissal of the Weston character is too simplistic, and also reeks of liberal virtue-signalling of the “I’m soooooo not-racist” variety. Weston is partially sympathetic in the same way as Derek Vinyard in American History X (though less so, since Vinyard is more principled and less criminal) – insofar as he values ideals over money, and also because he is a disciplined man, like Rollins himself.

In an interview from MTV’s 120 Minutes in 1992, Rollins relates that he was a troubled kid who was put on Ritalin because he was always acting wild. (He doesn’t relate the other part of that story: that he was being abused because he was white. In the course of researching this article, I couldn’t find any instance of Rollins putting two and two together and saying that being picked on for being a white minority was a reason for his having behavioral problems as a child.) It was only after he was sent to a disciplinary school, Bullis Prep in suburban Washington D.C., that his situation changed for the better. Specifically, he had the benefit of a mentor, his history teacher Mr. Pepperman, who took young Henry under his wing and introduced him to weight-lifting.

The story of how Mr. Pepperman helped the young, misguided Rollins to gain direction, focus, and confidence is quite inspiring. He wrote an article about it, and about his relationship to weight-lifting in general, called “Iron,” which was later retitled “Iron and the Soul” though not by Rollins himself. He also tells the story in detail in a podcast episode here. As he tells it in an L.A. Weekly interview:

“Around 10th grade, my fresh-out-of-Vietnam-vet history teacher Mr. Pepperman said, and I quote, ‘Henry, you are a skinny little faggot, you need to lift weights, and I’m going to teach you how,’ which was more input in life than my father ever gave me. (That’s just how people talked to you in those days.)

“He took me to the school gym and showed me basic compound lifts. He made me do a workout regimen and told me not to look in the mirror until he said so. I worked out from, like, October until Christmas vacation, and during the last day of exams he let me take my shirt off and look at myself. After that I threw out the Ritalin because I didn’t need it, my body is telling me to work out.”

In “Iron,” he says that during this initial work-out season, Mr. Pepperman would also surprise him at school by punching him in the solar plexus without warning, dropping him to the floor. It wasn’t until he could take the punches without effect that Pepperman gave him permission to look at himself and see the results of his workouts.

So what sorts of values, what kind of ethos, helped young Henry Rollins to grow into a strong and capable man? He was removed from the majority-black public school where he was bullied and abused just for being white, and placed in a private school in the suburbs – one which I doubt gave everyone a trophy just for playing the game. He was taught to be self-reliant and to stand up for himself by a decidedly un-PC disciplinarian and mentor. All of this seems to have been greatly to his benefit. So why is Rollins so averse to acknowledging that the right-wing view has validity and legitimacy?

Rollins’ article ends with some feel-good platitudes of the sort which might have made the young punk rock Henry puke:

“[Y]ou have to take it upon yourself to be an infinitely fantastic person every single day…. This century will be about incredible individuals.”

“Equality, tolerance and decency are not inherently American or human traits. They are values you choose to adopt and use or not. So, be amazing all the time.”

“Be amazing all the time?” Does he really believe this Hallmark card crap? Is this really what he would tell a kid getting bullied and abused the way he was in school? Is it the sort of advice that helped him – or was he instead helped by being told, “Henry, you are a skinny little faggot, you need to lift weights”?

The reality is that, as Jack Donovan writes in his aforementioned manifesto of muscular anti-liberalism: “This moral universalism makes men weak, vulnerable, and stupid.” To tell white people that the solution to America’s racial problems is for them to be “infinitely fantastic” and “adopt equality” is irresponsible and wrong. While tolerance and decency are fine virtues (I for one do prefer them to intolerance and indecency), they can become problematic as values when they are not held by all members of a society. Furthermore, I would argue that efforts to cultivate a little more “tolerance and decency” amongst, say, Chicago street gangs, would have a better net effect on black lives than yet another shaming sermon aimed at whites.

Donovan continues:

“[I]n a pluralistic or multicultural zone where there are many people from many groups, many of whom have different values, codes, and loyalties, there is a far higher likelihood that your generous assumption [of common values and social codes] will be wrong. You can choose to believe that everyone really wants peace and harmony, or that people all just really want to get along and follow the rules, but your belief would be wrong. Choosing to believe something doesn’t make it true.”

No, it doesn’t. And maybe, at some level, Henry Rollins knows that already, since he kind of gives the game away when he says that equality is not an inherent human trait.

True, indeed. In fact, AJ Weston couldn’t have said it better himself.

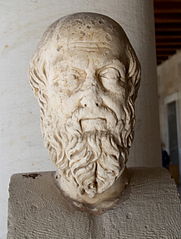

The Western Classical notion of identity comes to us from Herodotus’ Histories, written in the 5th century B.C. It’s from Herodotus that we have the story of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, told in the broader context of the entire Hellenic world’s successful resistance of the Persian invasion. In order to do that, the Spartans (Dorians) and Athenians (Ionians) had to overcome their differences and join together to defend what was common to both of them as Greeks.

The Western Classical notion of identity comes to us from Herodotus’ Histories, written in the 5th century B.C. It’s from Herodotus that we have the story of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae, told in the broader context of the entire Hellenic world’s successful resistance of the Persian invasion. In order to do that, the Spartans (Dorians) and Athenians (Ionians) had to overcome their differences and join together to defend what was common to both of them as Greeks.